History

St. Matthew’s was originally called Mather’s Church, but it soon became known as the Protestant Dissenting Church. This name held until 1814, when it was often called the Presbyterian Church. After 1820 it became known as St. Matthew’s Presbyterian Church, and the congregation kept that name until it became a member of the United Church of Canada in 1925 – it has been St. Matthew’s United Church since that time.

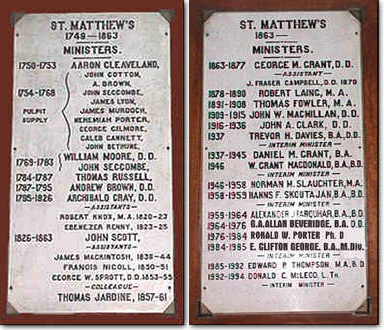

Application was made to Lord Edward Cornwallis for a Protestant Dissenting Church in 1749, the year of Halifax’s founding, and on Dec. 20 of that year the council granted a church site at the downtown corner of what is still Hollis and Prince streets. This most desirable location consisted of four lots granted to four single men who had made no effort to erect dwellings. The building of the church commenced in 1753 and in 1754 the Halifax Council voted the congregation £400 from the public expense account. The church was completed in 1754. From 1750 until 1754 when the church was opened, the congregation met for worship in St. Paul’s Church (Anglican). In the morning people went to St. Paul’s to hear Rev. John Breynton or Rev. W. Tutty in a service that lasted approximately three hours. In the afternoon, the same people attended the Dissenter’s service with Rev. Aaron Cleveland, their first minister, preaching. Rev. Cleveland was offered a piece of land at the corner of Barrington and Morris, but after three years with the Dissenters, he went to England and joined the Anglican Church.

The Glebe Land

The Glebe Land

One of the congregation’s favorite historical myths involved the granting and loss of land known as the Glebe Land. In 1751 the congregation was granted 65 acres of land between Oxford Street and the North West Arm in the area now bounded by South Street and Jubilee Road. In the summer of 1775 the minister of St. Matthew’s was Rev. John Seccombe. He was very outspoken about his sympathy with the leaders of the American Revolution, and during the summer a member of the navy and another of the military attended a service where they heard Rev. Seccombe pray for the cause of the rebels, then speak openly in their favour. On Monday he was brought before the Council and charged with uttering treasonable thoughts in sermon and prayer. He escaped with a severe warning, but at about the same time the Glebe Lands of the congregation were taken and given to Major-General John Campbell. Three members of the congregation, prominent businessmen named Malachi Salter, John Fillis, and W. Smith, were also charged with treason, tried and acquitted. Years later the congregation appealed to the Council for the return of the land. The application was turned down, but the equivalent acreage was offered in the Armdale area. This was refused and further applications by the church were ignored. Had the land remained church property until today it would be worth many million dollars. The congregation liked to say that Rev. John Seccombe preached the most expensive sermon ever heard in Halifax, although records show that actually the land was regranted because the congregation had not bothered to improve it.

Treaty of Peace

More and more Presbyterians joined the congregation until in 1783 there was open war between them and the Congregationalists, as the Dissenters of the milder type were then known. The battle lasted three years. The Dissenters wanted to call preachers of their choice from the New England States; the Presbyterians wanted a minister sent from Scotland. The Congregationalists wanted to sing the hymns of Isaac Watts; the Presbyterians wanted Psalms only. The Congregationalists wanted communion monthly; the Presbyterians wanted it once a year. The dispute was settled in a Treaty of Peace, signed Jan. 16, 1787. Hymns were to be sung, the minister would be sent from Scotland, and there would be communion four times a year. Regarding the latter, it was on early record that taverns sold rum on Sundays – and two Presbyterian elders were noted for serving communion in the morning and selling rum in the afternoon!

Cold comfort

It was very cold in the church during the winter months, as there was no heat whatsoever. The minister wore a long, heavy cloak over his regular attire, a heavy lined hood and fur mittens. Men attending church were so bundled and wrapped with scarves they could barely walk in. Women wore up to seven petticoats, many shawls and capes, and woollen gloves. The more wealthy had servants to carry in foot warmers made of iron that held live coals. Others had heated bricks wrapped in blankets to supply warmth. Three women had fat poodles they brought to church and used as foot warmers. In 1795 fashions changed. Women wore but one petticoat, cotton instead of woollen hose, low shoes instead of ankle-high laced footwear, and low-necked gowns. Women caught cold and died from chills taken in church, so a stove was installed on either side of the sanctuary and stoked the night before a service to heat the building.

Services in those days were very long. A sermon could last one-and-a-half hours. Prayers, for which the congregation stood, lasted from 40 minutes to an hour. An intermission was always given halfway through the prayer so that the infirmed might sit and be rested.

There was no Garrison Chapel in Halifax for years, so the military sat in the gallery at St. Matthew’s – soldiers on the right, artillery and engineers on the left. As the artillery wore white starched trousers and blue jackets with long tails, they made a fine appearance – but if the men were out late on Saturday night, the long service was apt to make them sleepy. A Sergeant-Major always stood in the centre of the gallery with a big pole, which he used to prod awake any unfortunate who started to snore.

Pew rents

Pew rents

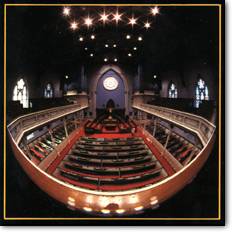

The best pews in St. Matthew’s, which rented for $144 per year, were to the left and right of the sanctuary against the walls. Those next to them rented for $100 per year. In the centre were long benches without backs, which were free seats for the poor and for single women and men. Pew rents were paid quarterly and if payments were not on time, the pew was auctioned. During the period from 1784 to 1850 all the leading businessmen of the town attended St. Matthew’s and a man’s credit in Halifax was judged by where he sat in the church.

Saving the best for last?

Saving the best for last?

In the period 1784-1857 morning service at St. Matthew’s began at 9 a.m. with a recital of the bills on hand asking for remembrances in prayers. A member might ask the congregation to pray for his wife, mother or child who was ailing. Another might ask for prayers on behalf of members of the family at sea, or prayers for a son or brother gone to the United States and not heard from. As the Bible chapter was read, it was explained verse by verse, and that might take the better part of an hour. Afternoon service began at 2 p.m. and it was then that matters of offenses were heard. The minister would read from the pulpit charges of slander. Mrs. White might accuse Mrs. Black of spreading false rumours, and would have witnesses to back her statements. Mrs. Black, if she had any hint of such proceedings, would have her own witnesses. After slander cases came cases of debt: one member would name another who owed him but would not pay. Third were charges of flirtation: a wife would charge another of flirting with her husband. Last in the list were charges of drunkenness, and these were mostly made by the minister.

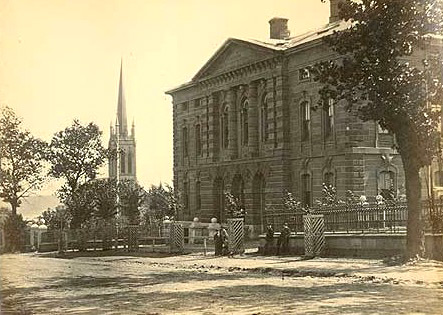

The church was burned on New Year’s Day in 1857 along with many other buildings. The congregation wished a new location nearer the residential area and purchased the site of an orphanage from Bishop Binney, the site of the present church near the corner of Barrington Street and Spring Garden Road.

Plain Jane

Plain Jane

The choir sang in the gallery and was trained by Mr. Henry Hill. He had three beautiful daughters who were good singers, and also Jane, who was not beautiful and who could not sing. The minister then was a young bachelor who admired one of the trio of beautiful singers to such an extent that he often gave out the hymn beginning “Unto the hills around do I lift up my longing eyes.” The congregation enjoyed such moments, but Henry Hill frowned on the young man, who was not highly paid. One summer evening, Mr. Hill dozed through the sermon, began dreaming, and was nudged awake as the hymn was once more announced. In his fuddled state he shouted: “It’ll be Jane or none!”

Original material compiled by Dr. William R. Bird, notable Nova Scotian author and historian.